When you first set up a limited company, it will invariably be purchased “off the shelf” with a ready-made set of ‘articles’. The articles are the constitution of the company.

They will either be the standard form ‘model’ articles published from time to time pursuant to the Companies Acts, or a version of those articles as modified by a third party – usually the incorporation company through which you purchased the company, or possibly your accountant or other advisor.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the model articles are basic. Moreover, they are limited to the essential items of governance and functionality which are regarded by the law as prerequisite for operating a company. These are: the creation of shareholders and directors; the respective powers, responsibilities and decision-making of directors and shareholders; basic provisions regarding shares and distribution of any profits; and a few administrative provisions. It is no business of the Companies Acts (pardon the pun) to be concerned as to whether you can operate the company strategically, favour particular shareholders or indeed resolve the myriad of problems and disputes which might arise.

A shareholder agreement (“SHA”) is a contract between the shareholders – and often, although not necessarily – the company itself. Unlike the articles, which are a public document available for scrutiny on Companies House, this is a private document between the shareholders only. It sets out the rights and responsibilities of the shareholders and, subject to some fundamentals, can be drawn-up in whichever way the shareholders wish. It is usually within the SHA that the shareholders, if they are sensible, make provision for a number of issues which the model articles say nothing about. If any of these issues might be important to your company one day, you should have an SHA and a set of articles which complement it.

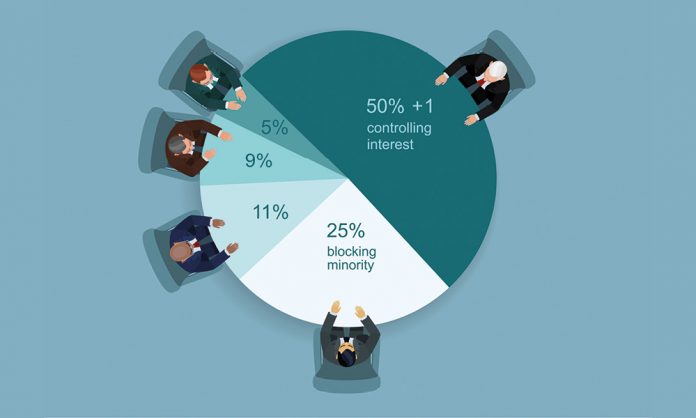

Ultimate control – Articles can generally be amended by special resolution (75% or more of the members who are present and vote at a general meeting). An SHA can require a “super-majority” for approval of certain important decisions. That super-majority can be calculated to ensure that control vests (or indeed doesn’t vest) in a relevant proportion of the total shareholders, or even that 100% approval is required. A supremacy clause can then ensure that in the event of a conflict, the SHA overrides the articles.

Board control – An SHA will usually make provision for the number and make up of the board directors, often providing shareholders with a right to appoint a certain number of directors to the board. This is key in ensuring that a shareholder has some day to day influence over the company.

Share transfers – An SHA can make provision for permitted transfers (shareholders having the right to transfer existing shares to others, often for tax advantageous reasons); voluntary transfers (how shareholders will be permitted to dispose of their shares); and automatic transfers (the circumstances in which shares will be forcibly removed, such as in the event of a shareholder breaching a duty to the company or harming its interests).

Transfer restrictions – An SHA can give the shareholders greater control over each other, as well as protection from undesirable third parties becoming involved in the company. A Buyback right will enable the company to have the exclusive right to buy its shares back in the event of a transfer situation arising. A right of first refusal will allow remaining shareholders to have first refusal, usually in proportion to their existing shareholding, of shares which are being offered for transfer.

Drag and tag provisions – Imagine a majority shareholder wishes to sell their shares to a third party, but the buyer insists on acquiring 100% – otherwise the deal will fall through. Drag provisions enable the majority to force minority shareholders to sell under the same terms and conditions. Conversely, Tag provisions ensure that minority shareholders can join a transaction on the same terms where a majority shareholder is selling their stake.

Information – What rights do shareholders have by default to company information? Very little, and only on an annual basis. An SHA can ensure that shareholders get the information they require at the frequency they require.

Confidentiality and restrictive covenants – Shareholders will often have access to confidential information and trade secrets. Without an SHA, the company and other shareholders will have to rely on the basic common law obligations in relation to these important issues. However, an SHA can restrain the shareholders in whichever way the shareholders, including preventing them from working or dealing with competitors in the future.

Deadlock – Sometimes shareholders will reach an impasse on an issue and be unable to proceed, potentially threatening the very existence of the company. An SHA can ensure that there is a mechanism for resolving such disputes which will allow the company to move forward. This may include a put option (entitling a shareholder to sell their shares by a pre-determined formula) or a call option (entitling shareholders to compel a shareholder to sell their shares) or even a shotgun clause (a mandatory scheme which operates either to force a shareholder to sell their shares or to buy out the offeror at a price determined by the offeror).

Anti-dilution provisions – Without an SHA, shareholders are vulnerable to dilution of their interest upon the issuing of new shares – either in terms of their relative ownership compared to others (% dilution) or in terms of value (economic dilution). Rights of pre-emption entitle shareholders to acquire new issued shares on a pro-rata basis in order to maintain their proportional ownership of shares. Full-ratchet and weighted-average provisions allow shareholders to retain their economic standing.

As can be seen, the absence of a well-drafted SHA means that none of these very real and common situations are catered for. It is often the case that the first time a shareholder reads a company’s articles is when a serious problem arises, by which time it is invariably too late to avoid either serious prejudice or an expensive dispute. Agreeing all of these matters in advance and when relationships are sound is undoubtedly the best approach.

Call Paladin on 0345 222 0 111 for advice and assistance with all shareholder and boardroom matters.